The World is a “Business Ecosystem” Managed by Politicians

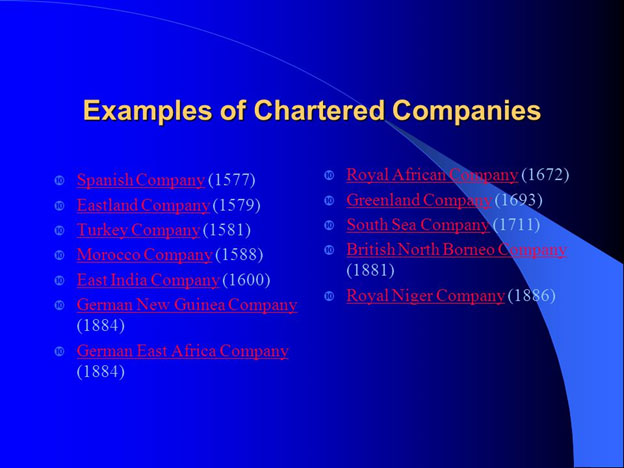

Part of the reason for the success of countries that have either made up ground or surpassed Western nations is that they get it. They get the fact that commerce is the business of the world’s nations. At the risk of over-simplification, the profit from supplying goods and services consumed by societies around the world is the lubricant of politics and economic development. Politics exists, as it always has, to manage the interaction of people in society and the business of society. “Export-Oriented Industrialization,” the vehicle that Asian countries have ridden to success, is a modern reincarnation of medieval-era chartered companies that European nations employed to devastating effect in their climb to global industrial and economic supremacy.

In the modern era, the Asians have evolved business conglomerates similar to the mercantile companies and the U.S Trusts of the 19th and early 20th century. One of the most well-known of U.S Trusts is Standard Oil Trust of John D. Rockefeller. A key difference between U.S and other business conglomerates including the mercantile era chartered companies is the private nature of U.S conglomerates. Business conglomerates of other countries, including European countries, tended to have varying levels of government involvement. The Japanese evolved a type of trading company known as sogo shosha. The sogo shosha is a business arrangement that evolved from earlier Zaibatsu and Keiretsu. The companies were responsible for marketing Japanese goods at home and abroad. They established the foundation of Japanese economic success.

The major original sogo shosha[1] include Mitsubishi, Mitsui, C. Itoh, Sumitomo, Marubeni, Nichimen, Kanematsu-Gosho, and Nissho Iwai Corp. In the late 1990s the sogo shosha controlled 10% of world’s exports and over 50% of Japan’s overall trade. Similarly, the South Koreans built their free enterprise system of “guided capitalism” on the backs of companies who, like their Japanese cousins, were multi-faceted trading companies that manufactured processed, exported and marketed South Korean products. In South Korea, they are known as Chaebol. Some of the brands have become international champions like Samsung, Hyndai, LG, Daewoo Shipbuilding, SK, etc. Taiwan also evolved business conglomerates known as the Quanxi qiye. Although not as famous as the Japanese and South Korean version they played a key role in transforming Taiwanese economy. Examples are Formosa Plastics, Linden International, and China Trust, etc.

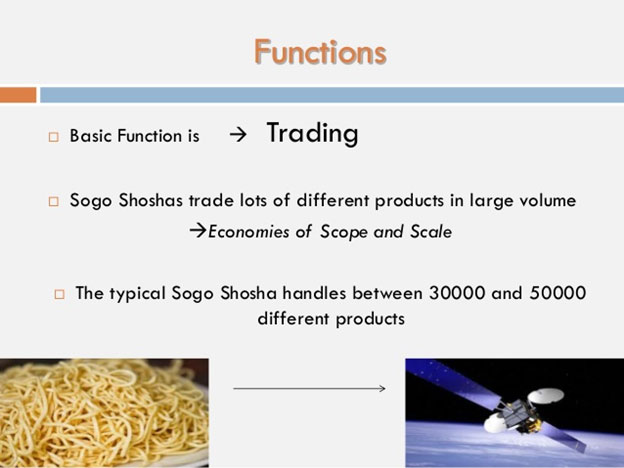

Fig. 1 Typical Functions of a Japanese Sogo Shosha

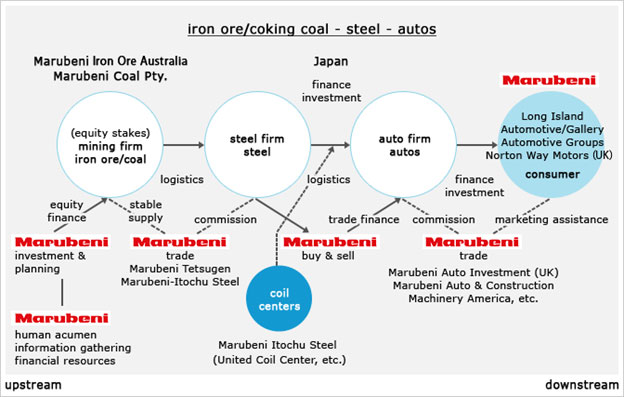

Fig.2 Marubeni, a Japanese Sogo Shosha’s Steel Supply Value-Chain

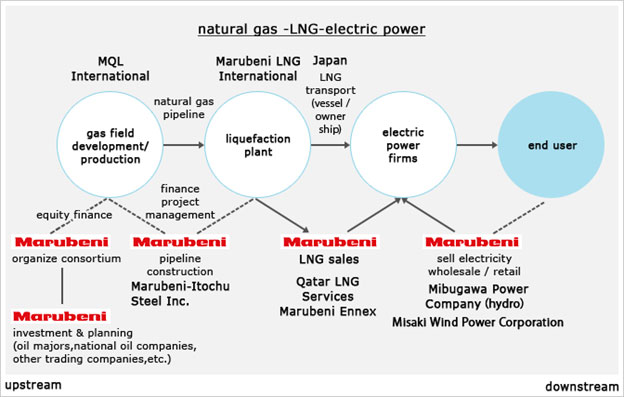

Fig.3 Marubeni, a Japanese Sogo Shosha’s Energy Supply Value-Chain

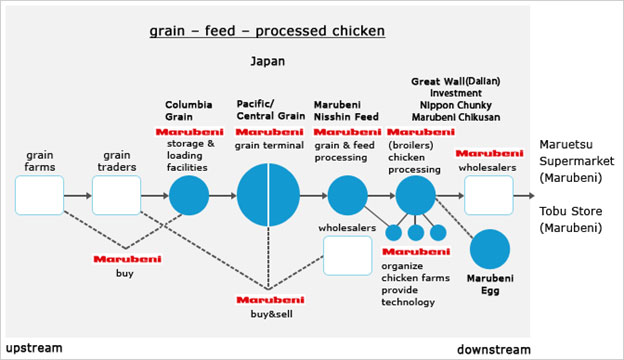

Fig. 4 Operating Divisions of Mitsubishi, a Japanese Sogo Shosha

[1] https://www.marubeni.com/research/report/industry/japan/data/shoshaexp2.pdf

Chartered Companies + European Ambition = Economic Power

Trade created the British, French, Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese empires. From the era of European exploration, beginning in the 13th century, the Western world set the template for the world in which we live today. Colonial rule did not start as a public policy but rather as an entrepreneurial venture. In India, the British East India Company (see feature on British East India company), a private chartered business was the government until the Indian Mutiny of 1857. After which the British government decided the territory was too large and its politics too combustible a cauldron to leave to commercial interests. Prior to the British Government taking over political management of India, the East India Company was the administrative body and had its own army. A famous alumnus of the Army is Arthur Wellesley, the First Duke of Wellington, whose career gained momentum from his service in India. Through successful military campaigns, he was very instrumental in expanding the company’s territory and eliminating France as a competitor for the territory. He later became famous for his victories in the Peninsular Wars and over French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte at the battle of Waterloo.

The East India Company sold English manufactured goods, such as fabrics made from cotton in India. The fabrics were produced from cotton imported from America. The payment for cotton fabrics exported to India was made with Indian Opium which was sold to the Chinese to pay for tea and other Chinese exports to Great Britain. Chinese objection to the sale of Opium in China led to the two Opium Wars from 1839 to 1842 and 1856 to 1860. In the British Parliament the rationale for the argument in favor of the wars was free trade. Several former employees of the British East India Company became British Prime Ministers, including afore mentioned Arthur Wellesley, First Duke of Wellington. Thomas Pitt, another renowned former employee, was progenitor of two British Prime Ministers, William Pitt, the elder and William Pitt, the younger. The Pitt family fortune was made in India through the East India Company.

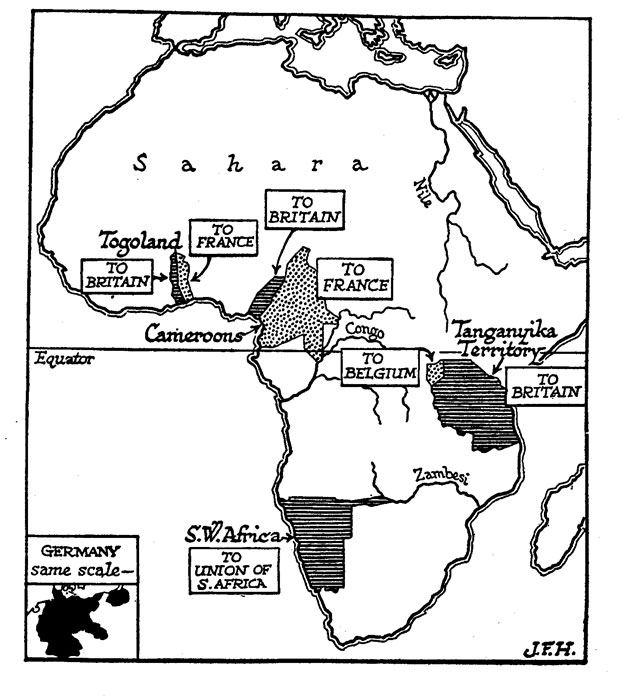

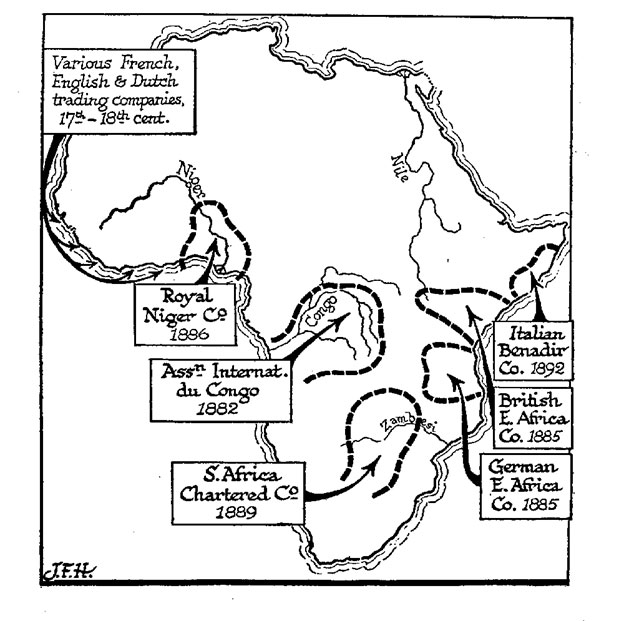

The Dutch East India Company colonized Dutch East Indies, present day Indonesia, and spurned Royal Dutch Company when oil was discovered. The company became Royal Dutch Shell after Henri Deterding merged Royal Dutch with Marcus Samuel’s Shell to form the company known today as Royal Dutch Shell. Colonization of Africa was carried out in much the same way by commercial interests of entrepreneurs who were just looking to make a buck. Two prominent names and their chartered companies in the African colonial scene are George Tubman Goldie’s Royal Niger Company and Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company. Much of the socio-political landscape of Africa is directly attributable to the exploits of the two entrepreneurs and the chartered companies they used to carry it out.

Chartered Companies in Africa

European Chartered Companies as Trading Companies in Africa

Africans Misjudged the Purpose of Independence

Unlike Asians, who were well acquainted with the commercial enterprise-relationship that Western “chartered” entrepreneurs developed and employed to subjugate their nations, African leaders did not. In their thinking, the raison d’être of independence was to capture the prize (political authority) so that they can enjoy the benefits they saw the Europeans enjoying in their societies, hence “our time to chop.” What they failed to realize was that European administration of colonies was a facade to ensure that commercial enterprises of the colonial nation had a secure and unencumbered transactional macrocosm. For Europeans, colonial rule was strictly about enriching the home government through their business enterprises. The enrichment was through goods, services and jobs that the business enterprises created for the home country of colonial governments. The accommodative environment in which colonial business thrived was braced by willingness to apply blunt trauma of military power when and if necessary.

It bears noting that after independence, the original owners of many colonial-era companies, aware that military protection had been lost in the process, were anxious to sell a lot of the companies. The process of wholesale withdrawal from post-independence African nations brought the late Mr. Roland “Tiny” Rowland and his company, Lonrho, into the affairs of African states.[1] “Tiny” Rowlands was aided and abetted by the British colonial office and British Establishment, in his acquisition of the companies that were put up for sale, in an effort to perpetuate “empire by other means.”

Tiny Rowland created a byzantine web of almost 100 companies throughout Africa, including the Ashanti Goldmines. He corrupted African political leaders–there’s public video of him handing an envelope to a political leader—in full view of cameras. He fermented strife, played one side against the other in civil wars and cut a broad swath of fraudulent dealings involving mineral exploitation in newly independent African countries. He violated sanctions in order to trade with then-illegal regime of Ian Smith, Rhodesia, and falsified financial statements used to justify high stock price for Lonrho on the London Stock Exchange. In short the man, as they say, was a piece of work. In the scandal of the “Lonrho Affair” in 1973, then-British Prime Minister Edward Heath made the now-iconic reference, that Tiny Rowland was “the unpleasant and unacceptable face of capitalism.” Tiny Rowland enriched himself at the expense of very poor African people who were betrayed by their leaders. On his death in 1998, his estate had a value of more than £220 million (pounds). He made out quite well while the trail he left on the continent is a mass of impoverished African people.

The Syndrome of “Our time to Chop”

After independence, African people, rightfully, were overwhelmed with joy at having captured government (the prize) but were totally oblivious to the imperative mission of nation-building, which is the purpose of self-government. Everyone was interested in the income from commodity exports because it was known to be an important contributor to the resources that the colonial administration used to run the government. In the post-independence period, it immediately became the fountain from which politicians sought to enrich themselves. The struggle for the “prize” and the propensity of so-called leaders to allow externalities to manipulate them was the genesis of incessant post-independence civil strife in many countries. The misguided approach to governance set the tone for the Africa we all know today. One in which the overriding goal is the struggle to capture the (prize) government so that the victors will have “our time to chop”. Political careers were not founded on the notion of contributing to developing society so that the country and people can prosper. While the creators of what has become known as the Asian Tigers sought to build their countries, African leaders sought “our time to chop.” Therein lies the difference between the Asian success story and the African narrative of failure.

The subconscious transformative sea-change needed in the mindset of leaders, therefore, is an overwhelming “I get it” understanding of the purpose of self-government. That self-government and political power that it spurns is a responsibility. A call to protect, preserve and defend the citizens. Not a mandate for “our time to chop;” to steal the people’s seed capital and marginalize their futures. Like the late Park Chung Hee of South Korea, the late Deng Xiaoping of China and the late Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore, African leaders should assume power bearing a mission statement reflecting the great need of their countries: To build successful societies in which everyone will have an opportunity to prosper in countries that are able to feed and defend themselves. It is a mission statement and a social-political contract requiring the total focus, energies, and abilities of true leaders and statesmen.

This post first appeared in Unleash Africa

[1] http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/99719ddc-bd38-11e2-a735-00144feab7de.html#axzz3QA2zfkBQ