Patriotism and Profit: Creating Champion Companies in African Countries (Part I)

by John I. Akhile Sr

Champion companies are companies that develop products or evolve a business model that becomes a ubiquitous brand known throughout the company’s region and, in many cases, the world. A few random examples of champion companies/brands are: Boeing, Toyota, Walmart, Mitsui, Sony, Mercedes Benz, Itochu, LG, Hon Han Precision (aka Foxconn), Apple, IBM, Microsoft, Samsung, Citibank, Unilever, Land Rover, Mitsubishi, General Motors, Nissan, HSBC, Exxon Mobil, Hyundai, BMW, Sumitomo, Deutsche Bank, Bayer, Volkswagen, etc. Every successful nation has developed on the back of champion companies. (1) Champion companies are purveyors of goods and services needed by global consumers.

European champion companies financed and or pioneered the age of exploration and colonial rule. The first industrial revolution created new champions that in many cases supplanted the original champions that emerged from exploration, discovery, conquest, and colonial rule. They have since also been matched or eclipsed by champions in services, including banking, insurance, accounting and management, computer, hardware, and software. The process continues.

In Asia, Douglas MacArthur abolished the Zaibatsu because of their role in supporting Japan’s then-war-mongering culture, but, secondarily, to sell their closely-held assets in an effort to liberalize the economy and spread the wealth to more Japanese. It was replaced by the Keiretsu, defined as loosely affiliated organizations. Some describe it as subsidiaries. The Sogo Shosha emerged as the most direct replacement of the Zaibatsu in terms of their economic strength and influence. While the Keiretsu are akin to subsidiary companies, the Sogo (sales and manufacturing) Shosha (combining many sales and manufacturing) is akin to a holding company. Some of the original Zaibatsu are also Sogo Shosha. Among them are Sumitomo, Mitsubishi, Nissan, and the very first of the original Zaibatsu, Mitsui. Sogo Shosha evolved into the most efficient trading conglomerates. The Sogo Shosha was and remains Japan’s sales force, carrying Japanese products to the world. In that context, the Sogo Shosha is the architect and builder of modern Japan’s post-WWII prosperity.

South Korea’s version of Japan’s Sogo Shosha is the Chaebol. The Chaebol of South Korea, like their Japanese counterpart, is responsible for much of the new South Korea. Samsung produces about 15% of South Korea’s GDP. Among the Chaebol are some of the world’s most successful Champion companies. They include Samsung, Hanjin, Lucky Goldstar (now LG), Hyundai, SK Holdings, Hanwha, Daewoo, etc. The same experience is evident in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, although the modality of how companies participated in the economy and the interventionist role of the two governments is quite different.

About Chaebols of South Korea: “Traditionally, the chaebol corporate structure places members of the founding family in ownership or management positions, allowing them to maintain control over affiliates. Chaebol has relied on close cooperation with the government for their success: decades of support in the form of subsidies, loans, and tax incentives helped them become pillars of the South Korean economy. Although more than forty conglomerates fit the definition of a chaebol, only a handful wields tremendous economic might. The top five, taken together, represent approximately half of the South Korean stock market’s value. Chaebol drives the majority of South Korea’s investment in research and development and employs people around the world. Samsung Electronics, the largest Samsung affiliate, employs more than 300,000 people globally (more than Apple’s 123,000 and Google’s 88,000 combined).”

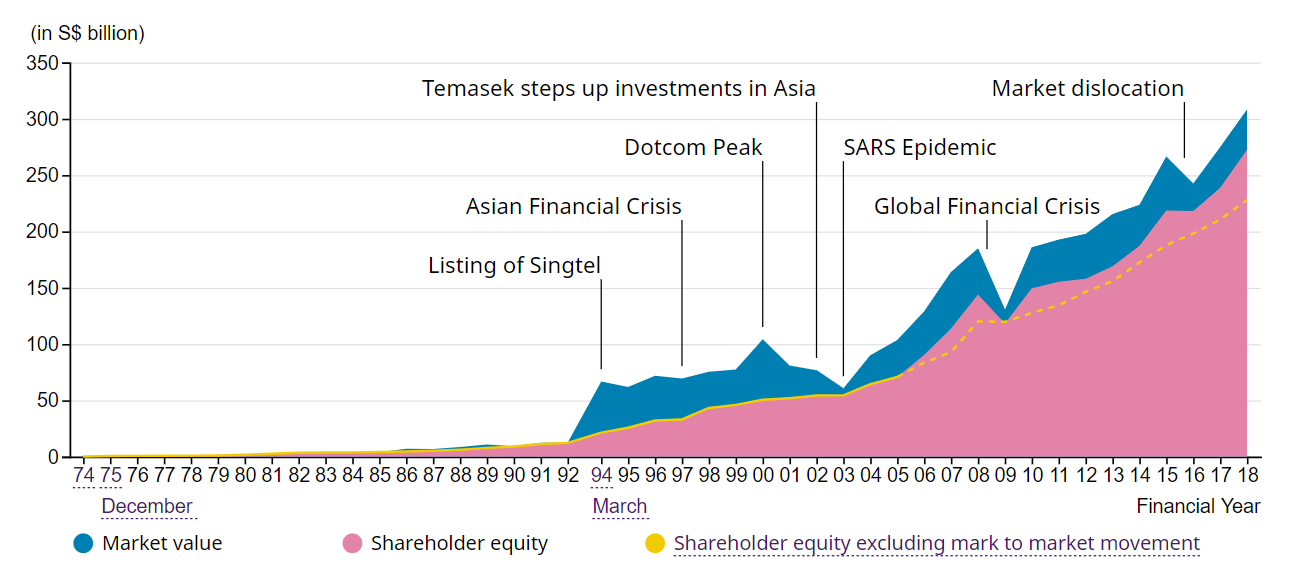

In Singapore, the government of Lee Kuan Yew left nothing to chance. They developed an industrial shell, Jurong Industrial Estate, now Jurong Town Corporation (JTC), of ready-made industrial space and deployed a team of salespersons to Western nations and elsewhere to fill them. The government also invested in a lot of companies that chose to locate in the fledgling estate. JTC has become one of the world’s most successful mixed-use, work, play, and live environments. The investment that Singapore made in the companies is the foundation of Temasek Holdings. Today, the company has assets under management of more than $300 billion dollars. It is a remarkable achievement for an idea that was meant to help reduce unemployment floated by the late “super-minister” of Singapore, Dr. Goh Keng Swee.

This brings the narrative to Africa and African countries. Between 1960 and 2000, Asian Tiger nations established their gravitas. The champion companies of the countries grew out of the era. They are now established. Foxconn, Apple’s manufacturing partner, is a Taiwanese company. Foxconn has a sprawling manufacturing facility in China that employs more than 300,000 people during peak iPhone release. The factory is a Final Assembly Testing and Packaging (FATP) facility. Foxconn is Hon Hai Precision Industry Company, doing business and trading as Foxconn around the world. The company manufactures a wide range of products including flat-screen televisions that are sold under many brands.

Most African countries have been independent for more than forty years. Some have been independent for more than sixty years. During the time, not one African company has emerged as a global champion company. In fact, one of the biggest issues facing many countries is that they are renting their private sector. The economic engine of their economy, the commercial enterprises and manufacturers are foreign-owned companies. The challenge is that as businesses, they are not inclined to business practices that are pro-development of the local economy. They are interested only in the business model that brought them to the country and not inclined to take risks outside of their main model of business. Not that that is the responsibility of business. However, like Samsung and other South Korean Chaebols grew and prospered through solving South Korea’s economic dilemma—lack of hard currency—by becoming exporters of South Korean products, African private enterprise is not similarly motivated by patriotism and profit. Like the Chaebols of South Korea, the Guanxi Giye of Taiwan, which includes Linden International, Foxconn, and Formosa Plastics, is Taiwan’s answer to lack of hard currency.

In general, it is assumed that if one complains of serious illness, they will go to the hospital to seek treatment. If one needs to improve a skill, they will seek out people who can help them to do so or books from which they will glimpse ideas that will help them to improve. If a sick person does not seek treatment and someone devoid of necessary skills does not seek out ways to improve, then it is safe to conclude that they are neither sick enough nor is their ignorance encumbering enough to force a change in attitude and behavior.

The unwritten consensus opinion in world opinion, in contemporary times, is that African people, their leaders, and societies are unwilling to confront and address the poverty of their societies in meaningful ways. People are quick to point to corruption as a foundational impediment to economic progress and it is. However, the greatest governance impediment is the total failure of African leaders to understand the game of economic and political maturation as practiced by successful nations.

The preponderance of corruption and corrupt activity in African countries is not a disqualifier in any given nation’s ability to achieve success. Even the most pervasively corrupt can still chart a path to success. That is because corruption is everywhere. It is rampant in Asia, the Middle East, in Europe, and the Americas. Every country is tainted by corruption. The West has had the most long-running bout with the menace and their experience is instructive. It creates a margin of error deficiency but a nation with the right mix of committed leaders and business can overcome the handicap of corruption and grow. Western nations are a very good example.

In Great Britain, arguably the founder of the modern world through the empire, there are untouchables. There are people who are above the law. The society shelters certain people—establishment types as they are known—from paying for their transgression. They sweep it under the rug. The whole edifice of empire and colonial rule was a sham perpetrated on helpless people by citizens of the UK backed by the government’s cannons. This includes selling opium to the Chinese. Two icons of the age of exploration and empire are Captain Morgan, a notorious pirate, and Cecil Rhodes, founder of apartheid.

French corruption is legendary and bald-faced. In this day and age, France is perpetrating economic colonialism on Francophone countries. Their reserves are held in France’s treasury, and their economic policy is dictated by France. Truth be told, Francophone nations are still colonies. The world, especially the Western alliance, refuses to acknowledge it. But perhaps, even worse is that the countries are also in acquiescence.

South Korea has wrestled with major convulsive corruption scandals that have led to many show trials and convictions. Not least of which is the Daewoo scandal that resulted in its restructuring. African countries have much that is positive to celebrate. From what is available, leaders can form partnerships with entrepreneurs and businesses and begin to craft a process that will lead to African countries gifting the world with champion companies over the next decades…to be continued in next month’s issue of Unleash Africa.