“It seems that the most predictable occurrence is that African countries especially in Sub-Saharan Africa are always ready to accept the illusion of “freebies” but fail to see the bait and switch. As the right hand offers “freebies,” the left hand is raping the country.”

There are many impediments to deep structured growth in African countries, the type that is not dependent on commodity prices. In order to begin to address them, it is necessary to find their cause or causes. Most people agree it is not enough to have countless rounds of conferences, meetings and declarations. At the end of the day, there must be a call to action that makes an impact on management and changes people’s lives for the better. Otherwise, these are just meetings and declarations for the sake of doing so rather than the desired result. For example, Africans have known that depending on the export of raw materials for resources to fund budgets is not a good idea because they are susceptible to the vagaries of commodity markets and, as a result, inherently volatile and unpredictable. Here we are more than forty years later still dealing with the same dependency. In many instances but particularly with petroleum exports, it is not unusual for raw materials to make up more than 90% of export revenues as is the case in Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, etc. This is unconscionable in any country with political leadership; yet the situation is very common in African nations.

There are many impediments to deep structured growth in African countries, the type that is not dependent on commodity prices. In order to begin to address them, it is necessary to find their cause or causes. Most people agree it is not enough to have countless rounds of conferences, meetings and declarations. At the end of the day, there must be a call to action that makes an impact on management and changes people’s lives for the better. Otherwise, these are just meetings and declarations for the sake of doing so rather than the desired result. For example, Africans have known that depending on the export of raw materials for resources to fund budgets is not a good idea because they are susceptible to the vagaries of commodity markets and, as a result, inherently volatile and unpredictable. Here we are more than forty years later still dealing with the same dependency. In many instances but particularly with petroleum exports, it is not unusual for raw materials to make up more than 90% of export revenues as is the case in Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, etc. This is unconscionable in any country with political leadership; yet the situation is very common in African nations.

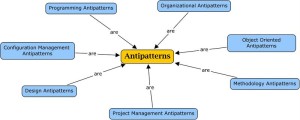

The scope of subject matter that hinders development is vast. They include infrastructure deficiencies in power generation, rail and road transport; development strategy, Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI), corruption, intra-regional and intra-Africa trade, poor service dispersal in the public sector, environmental sanitation and cumbersome enterprise formation process, to list a few. Many of the solutions have languished on shelves as soon as the conference, meeting or declaration about the issue enters the history books. It is a syndrome that I refer to as AntiPatterns of management and leadership dispensation in African countries.

AntiPatterns

AntiPatterns is a term borrowed from the software industry, but as we shall see in the African experience, is apropos. Due to the high cost and often long term gestation period of development, the software engineering industry has had no choice but to learn to manage the process. For companies, developing new proprietary software can be a path to great economic benefit but also potential peril. Unless managed effectively, the process can become the seed of the company’s demise. Given the existential challenge posed by software development, people attempted to reign in the lack of predictability by finding commonalities in good versus bad development results. As a result, two books came into being. One is about the traits of good software engineering pattern titled Design Patterns. The other is about the traits of bad software design process, an antithesis of the first one, and I think appropriately titled, AntiPatterns. Although one is not talking about software per se, the dysfunction that attends the implementation of accepted processes and objective aims attendant to the development trajectory of African countries, is akin to the challenges reflected in the concept of AntiPatterns.

The history of African experience post-independence spans many decades. For some countries, the duration is almost 60 years. For most, it is more than 40 years. It is not unreasonable to expect more to have happened during the four or five decades of independence. During that span, China rose from the depth of impoverishment to become one of the most successful economies in the world. Sadly, African leaders cannot open their hand fast or wide enough to extend a begging bowl for freebies. It seems that the most predictable occurrence is that African countries—especially in Sub-Saharan Africa—are always ready to accept the illusion of “freebies” but fail to see the bait and switch. As the right hand offers “freebies,” the left hand is raping the country. The focus is to shed a little light on the mindset that fails to search for internal solutions but is ever willing to welcome externalities bearing so-called solutions to their problems. This mindset is at the center of AntiPatterns plaguing African countries.

Paralysis of Analysis

Paralysis of Analysis, also known as Analysis Paralysis is the state of over-analyzing (or over-thinking) a situation so that a decision or action is never taken, in effect paralyzing the outcome.

Paralysis of Analysis, also known as Analysis Paralysis is the state of over-analyzing (or over-thinking) a situation so that a decision or action is never taken, in effect paralyzing the outcome.

Analysis Paralysis is why African leaders have “majored” in meetings and “minored” in action. An important exercise for the African Union in conjunction with the multilateral agencies would be to count the cost of all the meetings, conventions and symposiums that have been held to “address” development challenges in African countries since independence.

Competitive Ineptitude

Competitive ineptitude is the failure of political leaders to engage with the global community and their citizens to deploy the competitive advantage of their society in order to gain market share for their goods and services. A primary example, as mentioned earlier, is dependence on the exportation of raw materials. The inability to transition from the role of raw material exports to manufactured exports has left African countries with few options to redress high unemployment and poverty. It extends to idle man-power resources because adequat attempts are not being made to create a compelling story that will attract foreign companies to relocate plants to their country and create employment.

African leaders have to learn four words that successful nations know well: “The impossible is possible.” That is how mankind went to the moon, how South Korea built the most successful steel industry in modern history. It is how a city-state—Singapore—with less than 5 million people produced a GDP of more than $250 billion USD and has the third highest number of millionaires per capita in the world. Political leaders are responsible for ensuring that social advancement is taking place and that to the extent possible, society is achieving its potential. It requires leaders to be fully engaged in the process of scouring the globe for opportunities to advance the interests of their people. Solving society’s problems requires that leaders concentrate all their energies on seeking remedies. Lack of desire to vie for prosperity opportunities with other countries is the same as failing to show up for competition, and unwillingness to research solutions hiding in plain sight is political ineptitude.

Systemic Blindness

For our purposes, we will define successful societies as societies that work. The public sector does what it is supposed to do and the private sector, likewise, plays its role in society. Systemic blindness is not unique to African countries. In fact, every society that does not function properly usually has problems directly attributable to systemic blindness. Take the United Kingdom before Baroness Margaret Thatcher for example. British Telecom, one of her first privatizations, was a telephone monopoly in a country that had a very high demand for telephones. In any business model, it is an entrepreneurs dream. One would rightly expect the monopoly that has more demand than it can satisfy has happened fortuitously on a license to print money. Well, the reality was the opposite.

For our purposes, we will define successful societies as societies that work. The public sector does what it is supposed to do and the private sector, likewise, plays its role in society. Systemic blindness is not unique to African countries. In fact, every society that does not function properly usually has problems directly attributable to systemic blindness. Take the United Kingdom before Baroness Margaret Thatcher for example. British Telecom, one of her first privatizations, was a telephone monopoly in a country that had a very high demand for telephones. In any business model, it is an entrepreneurs dream. One would rightly expect the monopoly that has more demand than it can satisfy has happened fortuitously on a license to print money. Well, the reality was the opposite.

The company was not profitable; it could not deliver phones or efficient service and was a drain on the treasury. However, before Margaret Thatcher, every government simply ignored it. All of them left the inefficient system in place in spite of being fully aware it was not normal. Bell System, a private business in the United States, was modelling efficient and well run phone service. Instead, they abided the system for decades. That is a prime example of “systemic blindness.” Everyone in society had come to a place where the abysmal abnormality of British Telecom was considered the norm. Until Thatcher, a change maker came along and applied the “why curiosity.” Why are we doing it this way and not succeeding while those people are doing it another way and having great success? Why don’t we examine what they are doing and consider adopting it? Privatization was working very well in the telephone industry in America.

Systemic blindness, therefore, is a situation in society that is abnormal compared to its successful model in other societies or environments. It is a hydra-headed monster whose influence can span the range of activities in society. It also includes the failure to eliminate incompetence and rent-seeking from public sector activities. It is very difficult to sell anyone that the country is serious when there is rampant dysfunction. In some countries, the dysfunction starts from the airport terminal where people come into the country. Processing people entering the country stretches out to hours. One experience in an African country involved standing in line to clear customs for almost as long as the flight there. Civil service delivery is another major dysfunction that people accept. Year after year, the interaction with the civil service creates a conundrum for the citizens and visitors alike. It is okay for an abnormality to exist when there are no comparable models against which to judge the performance. In the case where there are comparable models however, it is incumbent on leaders to hurl all their energy at matching the control model. Accepting the dysfunction as normal is the core of systemic blindness.

In Part 2, we shall illustrate more examples of AntiPatterns and share SuccessPatterns to model by countries that that will eliminate them.